One idea I gleaned from reading Chuck Wendig’s THE KICK-ASS WRITER recently was that of tent poles. As in, stories need them. Without them, the plot falls over, just like a large tent with no poles.

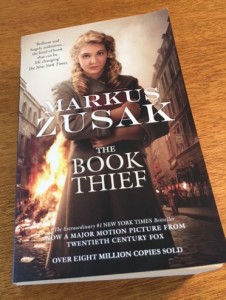

Immediately prior, I’d read Markus Zusak’s THE BOOK THIEF for the very first time. (Yes, yes. I know I’m probably the last person on the face of the Earth to do so. I’ve been busy, okay?)

And you know what? Looking back at THE BOOK THIEF, I could see what Wendig was getting at. I could see the tent poles! (Exclamation point needed because I was pretty excited; this had never happened to me before…) And I wanted to share some of my thoughts with you. So they’re below. (Warning: long post ahead! Also, spoilers. Just in case anybody else on the face of this planet hasn’t yet read the book or seen the movie and manages to somehow find this post):

Liesel. As readers, we are first introduced to her on a train. I don’t know about you, but my first thought about ‘trains in Nazi Germany’ is ‘Jews on their way to prison camps’, with all its associated misery and horror. This train journey is not one of those, but Liesel unwittingly watches her younger brother die, so the misery and horror are still there. Then her mother is forced to abandon her, which tugs at our heartstrings and immediately turns her into a sympathetic character, if she wasn’t already. Obviously, Zusak needed his protagonist to be German. But she needed a point of interest to keep her separate from the ‘oppressive’ Nazi rulers. So Zusak also made her the youngish daughter of Kommunists, the underdogs, and therefore making complete our view of her as someone to be pitied. Interestingly, Zusak gave his main character the same name as the eldest daughter in THE SOUND OF MUSIC. So I also had an instant association with “an innocent, in a coming-of-age” story. Liesel also needed to be illiterate at the beginning, to develop her love of books and likewise, her love for ‘Papa’, Hans Hubermann.

Liesel. As readers, we are first introduced to her on a train. I don’t know about you, but my first thought about ‘trains in Nazi Germany’ is ‘Jews on their way to prison camps’, with all its associated misery and horror. This train journey is not one of those, but Liesel unwittingly watches her younger brother die, so the misery and horror are still there. Then her mother is forced to abandon her, which tugs at our heartstrings and immediately turns her into a sympathetic character, if she wasn’t already. Obviously, Zusak needed his protagonist to be German. But she needed a point of interest to keep her separate from the ‘oppressive’ Nazi rulers. So Zusak also made her the youngish daughter of Kommunists, the underdogs, and therefore making complete our view of her as someone to be pitied. Interestingly, Zusak gave his main character the same name as the eldest daughter in THE SOUND OF MUSIC. So I also had an instant association with “an innocent, in a coming-of-age” story. Liesel also needed to be illiterate at the beginning, to develop her love of books and likewise, her love for ‘Papa’, Hans Hubermann.

Death. The narrator. He didn’t introduce himself, so as readers we were forced to intuit this piece of information – and it’s always good (so says Chuck) to make the readers ‘do some heavy lifting’. And so we do. As an outside spectator, still very invested in the happening events, Death was extremely useful, as he provided a supposedly objective view of Liesel. His being an omniscient immortal helped too. It was ‘expected’, almost, that at times he would refer to later events, and this glimpse into the future – or past, when he related the events of the Great War as it pertained to the backstory of Hans, and his debt to Max – also assisted the structure of the novel somewhat, alleviating any sense of ‘drag’ by the predominantly lock-step, week-by-week telling of the story.

‘Papa’. Hans Huberman, Liesel’s step-father. He is the first to be kind to Liesel, drawing her from the car the first time we see him. His sacrifice of sleep each night, and his teaching Leisel to read, and especially when he rescues her from humiliation over her completely-understandable bed wetting incidents, ensures he is cast in heroic light.

Rudy. The ‘best friend’. Boy-next-door, the same age (and therefore same class at school) but opposite gender. This meant that Liesel had someone to offer her support, but also have friction with. His desire to have her kiss him, meant she was seen – by him, at least – in a desirable light: and the fact that the kiss was unrequited spoke not only to her integrity but also gave both characters pathos, knowing from very early on that he’d die without ever receiving his heart’s desire. Zusak needed Rudy’s father, Alex Steiner, to be absent at the climax, so therefore he was conscripted. We are given the impression that his conscription was punishment for Rudy’s NOT going to war, so Zusak needed Rudy to be desired by the Nazis. Hence his blond hair, blue eyes and running talents. But Rudy needed to be unpatriotic, therefore his idolisation of not only a ‘negro’ athlete, but a famous American one to boot.

Max. Liesel’s other ‘best friend’, needed to add the element of danger. Max was a Jew, who Papa hid in the basement. Zusak ratcheted the tension in this situation because Max could easily have been discovered by Papa or Mamma’s own son or daughter – and their son was a brainwashed deeply patriotic Nazi. And although Max was captured – it would not have been realistic if he were not – he also needed to survive, the symbol of hope (otherwise, the book may indeed have been realistic, but would have been too dark to be palatable, I think).

The community of Himmel street. Himmel = heaven / sky. Himmel street was not heavenly, by any stretch of the imagination. But the community – with the exception of Liesel and Alex Steiner, Rudy’s father – was taken to heaven by Death, after bombs from the sky obliterated their street, killing indiscriminately. Zusak needed all of them to die, again, to make a distinction between them and Liesel, as her survival of this tragedy shows her inner strength. This event also tugs on our heart-strings, as by the time it occurs, we readers have spent the majority of the novel building strong emotional connections with these characters.

Isla Hermann. The Mayor’s wife, first introduced as the shadowy figure who watched Liesel steal a book from the remains of a bonfire. Her character was needed, as the person to take care of Liesel after her community had been obliterated. Therefore, Mamma needed a job (washerwoman) which would introduce her into the Mayor’s circle. And Liesel having a love-hate relationship with Isla not only gave more depth to both characters but also gave Zusak the opportunity to introduce the iconic symbol – the blank journal Leisel wrote in, which eventually became the book that Death carried as a reminder of his “Book Thief”.

Alex Steiner, Rudy’s father. For Max to find Liesel after the war, some part of the Himmel street community needed to survive. Therefore, Rudy’s father needed to be away at the time of the bombing. His being a businessman also gave Liesel a job after the war, where she could be found. Alex Steiner’s survival of the war also drilled home the idea of senseless tragedy – that Mr Steiner, who was in the most danger at the front, should survive to employ Liesel, and yet his entire family, neighbours and friends, who lay sleeping at home in their beds, who should have been safe, were all killed. It would also seem that Alex – not the Mayor – becomes Liesel’s replacement father-figure after Hans’ death. The juxtapositioning of these two characters is even poignant, given that Death had related Hans’ story, of his evading Death (through chance) at the front not once but twice. Thus Hans’ death is all the more tragic, and the senselessness of war is reinforced.

Overall, I loved the writing; the description was without compare. One image that prompted me to sit back and say “wow” referred to the blinds over the windows as ‘confiscating the light’. Death’s descriptions of the colours threw me a little, but not excessively.

Most events were a surprise, but not out of left field. It’s only when you consider it in hindsight, that all events can be seen to be necessary. And that, I think, was the beauty of this writing for me. That Zusak was able to masterfully craft a story, and write it in such a way that this reader, on her first time through, was hooked by the first chapter and unable to step away until after the final sentence.

Well, congratulations on making it to the end of an excessively long blog post! And what did you think? Were there “tent poles” I missed?